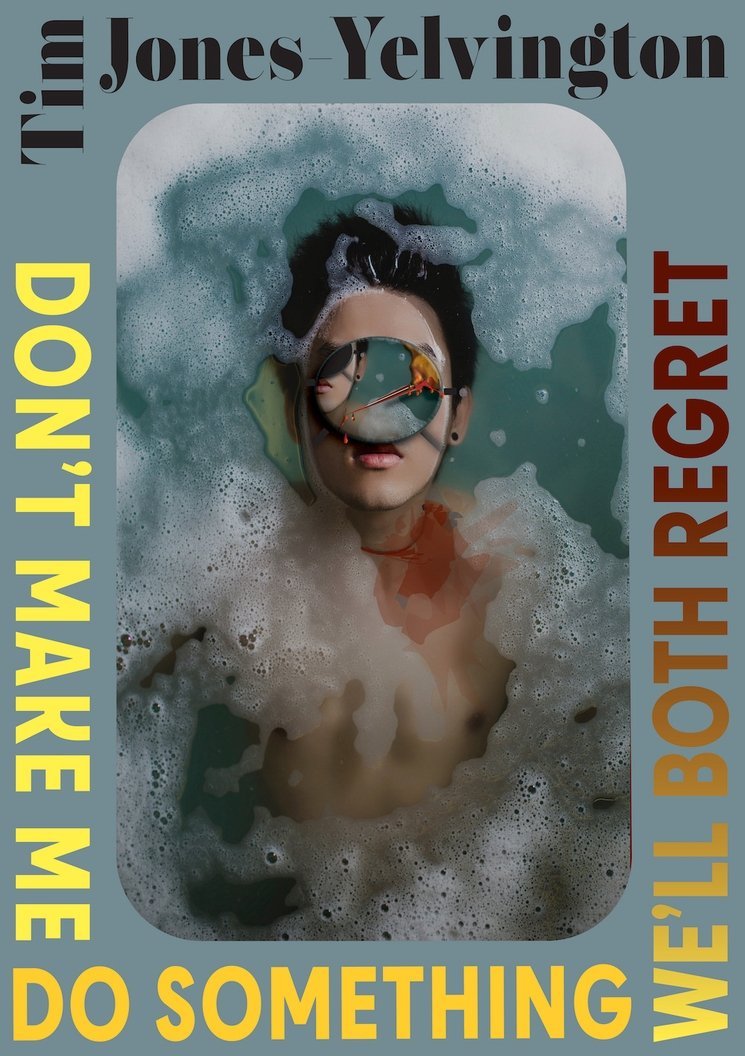

The central theme of Tim Jones-Yelvington’s new collection Don’t Make Me Do Something We’ll Both Regret is queer evil. Desire and malevolence are the twin impulses of many of the book’s deliciously vain, often cruel characters. As with Jones-Yelvington’s other work, these playfully audacious stories are as hilarious as they are unnerving, typically both at the same time. Recently published as part of Texas Review Press’s new Innovative Prose Series, edited by Katie Jean Shinkle, Don’t Make Me Do Something is also tremendously intertextual, drawing and riffing on texts as various as internet memes, fan fiction, the American Girl books, Dodie Bellamy’s Cunt-Ups, and the Judeo-Christian bible. I spoke with Jones-Yelvington over Zoom about vanity, narcissism, evil, dirty talk, and more. —Megan Milks

Megan Milks: You’ve been rather self-effacing about this book, or at least it seems that way to me, in terms of book promo and celebrating the release. And yet, the book is full of characters who are motivated by vanity. Vanity is a strong force in the book, and—to bring in the theme of this issue of Grimoire, Goth Narcissism, you have a lot of characters who could be considered narcissistic in one form or another. I’m curious about this. It seems like an incongruence—or maybe not. Do you see this as contradictory?

Tim Jones-Yelvington: I have three different answers. Should I try all of them?

MM: Sure.

TJY: One element of it is that for such a long time, I had a whole writing and performance practice that was very much built around leaning into and claiming and celebrating vanity and attention-seeking, and trying to build up this performance persona. It was wonderful, and I’m glad that I did it and I had a great time and discovered other ways of making. But I tried to make this pivot from doing that specifically within the context of literary work into actually trying to pursue drag in my life career, and I think there’s a sense of failure around how much that never really came to be and the time it took away from actually creating work. I think I’m still carrying that, so that’s where some of the self-effacement comes from.

Also, what I appreciate or value most has shifted as I have aged and settled down a little bit. I really enjoy the smaller, more intimate and more community-driven experiences now. So to do that kind of thing [promotion and events]—like trying to plan a book release party—is like trying to rev myself up to make sure people are there when there’s really only like five friends who I see regularly in Chicago anymore. It just feels a little overwhelming.

The third thing is this whole area around anxieties around the book politically and whether it’s conscionable. For a long time I had this sort of split between the parts of my life outside of writing that are very committed to radical social movement work, led by people most directly affected by intersecting issues with a focus on collective liberation, and then creating work that I feel like—it’s certainly not apolitical, it has a politic to it, but it is a sort of more vain and self-focused type of politics or more individual subversion or expression I guess.

The theme is queer evil, and that’s something that’s really appealing thing for me, like, leaning into the negative, or monstrous, depictions and stereotypes and weaponizing them. There’s something really personally freeing, expansive, and fun about that. I sometimes wonder: how much is my ability to do that without any fear of real material repercussions enabled by privilege? Is there a way I should be responsible for that? I get caught up in some of that and have to figure out how to get myself to where I can be a strong advocate of that work again.

MM: Evil and vanity are intimately connected in the collection. In a lot of the stories both start off as, or sometimes stay in the realm of, feeling like forces of resistance and resilience. But then, often, there’s a turn where you allow them to be truly monstrous. You’re not, like, playing at it. In some ways, you are, because it’s absurd and campy. I’m thinking in particular of “Limelight Memories.” The story ends with the characters (the One Direction wolf pack, I mean— and this is a plot spoiler) sacrificing their offspring to stay young. And this is one of the ways in which the story turns and gets to come across as grotesque and horrifying, and also campy. You’re working with fanfiction, crossing over into werewolf stuff; there’s just a lot going on that’s really exciting.

TJY: If I started grouping the stories, there are certain ones I think of more as play, and there are certain ones where the violence feels more “real.” Initially, I might have put that one more in the play category. That’s also one of the really camp-inflected stories. There’s a lot of different ways of thinking about or defining camp, but one of the ones that’s always been the most compelling to me, is this tonal destabilization where you kind of don’t know what to take seriously, and what should horrify you, or move you, or make you feel a certain kind of intensity, along with the big sweeping emotions the characters might be feeling.

Probably in all the pieces there’s a more complex relationship between play-evil, and “real” or more materially violent evil, that maybe I’m putting out there and not intending to resolve—wanting to make that part of the work of sharing the story with readers. Maybe that gets at the actual unresolved dilemma I feel over the work and the appeal of writing in these modes while also thinking about their real impact.

But in terms of queer evil, more generally, the way I’ve conceptualized it is that it moves through these different modalities.

The first batch of stories I tend to think of—the first two or three—as a more enraged or visceral violence that might be more directly motivated by the experience of an exclusion or marginalization or maybe having experienced a form of violence. The next section feels more to me about when desire is pathologized, becoming monstrous and that’s the love stories [laughs]. And then the section we’ve been talking about, where the One Direction story sits, I think of as more the Evil Queen Magic section, where it’s about the evil of using art to recreate the world in your own image. Again, that’s vanity in some sense, which may have consequences, but also can make something glamorous or glorious in some ways too.

MM: One more thing on the “Limelight Memories” story, which might be my favorite piece in the collection.

TJY: It’s mine!

MM: It’s also a sexual assault narrative, and that part of the story does feel like there’s more at stake. It’s handled with respect for survivors of sexual assault, and I noticed in the notes that the story is informed by narratives of survivors. I’m not familiar with this particular story of Horace Mann School.

TJY: Yeah, that school in the Bronx. I read this piece in The New Yorker. And this was something I discovered along with a lot of the celebrity memoirs I read when I was working on Strike a Prose, my last book, as well: I have this sort of fascination with how simultaneously deeply moved and disturbed but also entertained I am by a type of prose—and this is also maybe a kind of camp, I’m not sure—that has real trauma in it that you can feel and that needs to be expressed, but also has this element of outlandishness—that may even be a part of what really happened. There were really literary qualities to this story of this particular abuser at that school who had this theatricality to him that I was deeply fascinated by.

I still don’t know what made me think, “oh, let’s take sexual assault narratives from a prep school, male pregnancy, and wolf knotting One Direction fan fiction, and then a whole slew of old-Hollywood camp cinema references and put them together and see what happens” [laughs]. It feels the most “only I would have done this.” Maybe that’s why it’s one of my favorites.

MM: Somehow, the boy band as the container for all of these things seems totally believable.

TJY: Forcing these people together and exposing them to this machine they might not be ready for—that’s already all there. And then the violence and the camp and the intimacy with one another.

MM: Talk to me about “Teenagers Need.” I rarely respond to a piece of writing with a sense of moral crisis. But as I was reading this, you got me into that space of like, “I don’t know how to feel about this.” When I read in the back that you were working with [Dodie Bellamy’s] cunt-up method, that made sense. It did seem like you were juxtaposing a few different kinds of texts in Drew’s monologues. On the one hand, it’s so screamingly funny, I can imagine it as a performed text—in the same way that Cunt-Ups, if you read it out loud, is so funny—but if you’re alone with it on the page, it can feel quite unsettling; it’s kind of deranged in a way. What texts are juxtaposed in that piece?

TJY: In the cunt-up method, there’s four quadrants on each piece of paper. And you do it with at least two texts, and one of the texts is always something that has a pornographic element to it, and the pornographic text I used was One Direction flash fiction.

I internet-sourced pages and pages of sentences that began with “teenagers need” onto one page, and then I cut that up with the One Direction text. It’s interesting that it was the most disturbing and/or funny to you because I think I experience it as, oddly, the most tender and vulnerable. It feels more revealing to me of longing; the narrator’s in relationship to their adolescent experience. To me, the whole thing takes place in a sort of phantasmatic space.

The super erotic text that appears in those cunt-up sections, I’ve always experienced as pleasure or desire or eroticism being experienced by either the actual character—the Degrassi character, the Drew Torres character, or by the narrator of the story—and then directly transmitted through affect to the reader. I’ve more thought of it as auto eroticism and pleasure in a very direct way. Which is also honestly how I experience Dodie’s Cunt-Ups—there’s a political project to them, too, but I find it genuinely hot; this scrambled and defamiliarized language has a direct impact on my body.

MM: I’m loving what you’re saying about Dodie’s work and how it comes into this, too. There’s something really disembodied about the language, but it also does feel like dirty talk, in the same way that dirty talk sometimes just doesn’t make sense.

TJY: Actual dirty talk is rarely hot to me, but this weird kind of hybrid poetry mode is totally my experience of it. Both reading and writing it—taking meaning out of the traditional way really helps me experience it in the body way. Maybe there’s something in me that—while not being an adolescent and feeling power or privilege that I need to be mindful of with relation to them—also carries this residue of unfulfilled adolescence in my desiring. Or something like that.

MM: Some of the characters you have created are very explicitly predatory, older gay men. I’m curious what you would say to readers who might balk at reanimations of these tropes, which we are familiar with as antigay representations of homosexuality as pedophilia.

TJY: There’s a privilege to this, but I’ve never felt directly harmed enough by those tropes to feel uncomfortable doing that thing of claiming and weaponizing and throwing them back. Maybe this is a problem because it requires knowledge of another body of texts, knowledge not every reader will have, but I think those stories are in direct conversation with that queer transgressive literature lineage that I mentioned. I’m thinking from Dennis Cooper on back, you know, all those French people [laughs]. The decision that was intentional, was to take the expectation that it was going to be a sexual, predatory thing and then subvert it. So in the “Damn Daniel” story, it’s like, making it about fashion and the predator wanting a piece of youthful fashion, rather than wanting to do something sexual to them. With the “Alex from Target” story, it’s about jealousy of the romance that the younger character gets to experience, the older character wanting to control the narrative, and also to point out the violence of being able to control the narrative as an author. It’s not about wanting to sexualize Alex. Those subversions were really deliberate.

In terms of the negative tropes, I’m more like, “yeah, so what if I am?” most of the time. Not in a way of, like, actually having any desire to be predatory toward anyone, but definitely in that way of being like… I guess a concrete example would be: in this current awful, anti-trans grooming discourse, being like, yeah, I want to bring people into the community, into having access to information. But my first impulse is to take that groomer label and own it. You know what I mean? Like, like making T-shirts that say, “OK, groomer” and wearing them. That kind of anti-respectability politics is the most appealing to me.

MM: I feel like we have to talk about the Old Testament and your appropriations of biblical texts.

TJY: Jac Jemc blurbed this and in her email, she was like, “Do you know Sam Cohen? I also just blurbed her book and it had a queer Abraham story in it.” Mine is influenced by Christian summer camp, though, and hers is obviously very Jewish.

MM: Was this one what we published in The Account?

TJY: Yep. It’s also one of the two oldest pieces in the collection, the one that made me want to write a collection for this theme in the first place. I was like, “How do I take these two stories and put them together? What would that book be?” And when I started actually putting the stories together in an order, it was the one I had the hardest time figuring out where to put. It just didn’t go before or after anything or segue into anything in a way that felt natural. And then I was like, “Wait, what if it was the spine?” And the entire order of the collection locked into place after that, with the stories grouped loosely by theme under the different Testaments.

MM: It gives the book a strong shape and structure.

TJY: I’m so thrilled with what PJ did with the design, too.

MM: The whole book is really beautiful. What are you working on right now?

TJY: Two things. I have a project I started and put down for two years, one that I worked on really intensely in 2020. It’s probably the most directly New Narrative-influenced thing I’ve ever written, form-wise. It’s an anti-hero’s journey hero’s journey for strawberry Fanta in the midst of the pandemic.

MM: Oh yeah, you’ve mentioned this to me.

TJY: And then the other project is completely different. It’s a daytime soap opera.

MM: Like an actual screenplay?

TJY: I have a screenplay pilot. That was not the original plan. I got reconnected with my childhood love of daytime in 2021, and also got interested in a lot of the scholarship on it. I started wanting to create my own. The narrative parameters that are most interesting to me are tied to the challenge of keeping up a 52-week, continuous, uninterrupted, slowly pace, multiple-installments-a-week kind of format. This format is, like, an impossible thing to get produced in 2022. There’s never going to be any new daytime soaps in the United States ever again.

MM: Exciting.

TJY: It’s weird because all the stuff that I thought I had no interest in - like character and plot and stuff - I’m developing a deep interest in, but through this completely liminal genre.

MM: That makes so much sense to me. Side note: the crystal ball baby bump from “Limelight Memories” was one of my favorite moments I’ve had in my recent reading. So good.

TJY: [laughs] I can see the ways that speaks to some of your interests as a writer.

Tim “TinTim” Jones-Yelvington is a Chicago-based author, multimedia artist, and nightlife personality/drag performer. Their multi-genre novel Strike a Prose: Memoirs of a Lit Diva Extraordinaire was published by co•im•press. They are the author of two full-length fiction collections, This is a Dance Movie! (Tiny Hardcore Press 2016) and Don’t Make Me Do Something We’ll Both Regret (Texas Review Press 2022). From 2010-12, he guest edited [PANK]'s annual queer issue. By day, Tim works as Program Director for Foresight Prep, a summer leadership development program that empowers sustainability and social equity-interested young people to pursue their social change goals.

Megan Milks is the author of the novel Margaret and the Mystery of the Missing Body; Slug and Other Stories—a revised and expanded version of their Lambda Literary Award-nominated short-story collection, Kill Marguerite and Other Stories; and Remember the Internet, Volume 2: Tori Amos Bootleg Webring. Their memoir, Mega Milk: About My Name (and Family, and Fluidity, and Whiteness, and Cows) is forthcoming from Feminist Press in 2025. With Maria Crawford, they are the coeditor of We Are the Babysitters Club: Essays and Artwork from Grown-Up Readers; with KJ Cerankowski, they are coeditor of Asexualities: Feminist and Queer Perspectives. Born in Virginia, they currently live in Brooklyn.