When the Girl leaves the womb she is all red. Red and

sticky with oozing milk coating her tiny body. Her

mother, surprisingly alive, tilts her head back and

drinks her own labor sweat. Too salty to quench, the

father pours a whole pitcher of water onto mother and

child, the pasty white sick washes off in a moment.

The baby wails; upset, concerned when the air shows

no face, gives no announcement of its presence, just

enters and exits the lungs, fast and cyclical.

The village Hag waits outside the cottage window,

pacing and banging sticks together in the dusk. When

she hears the child’s first wail, the curl of her upper lip

rises like a sun; a girl, what a stupid mistake.

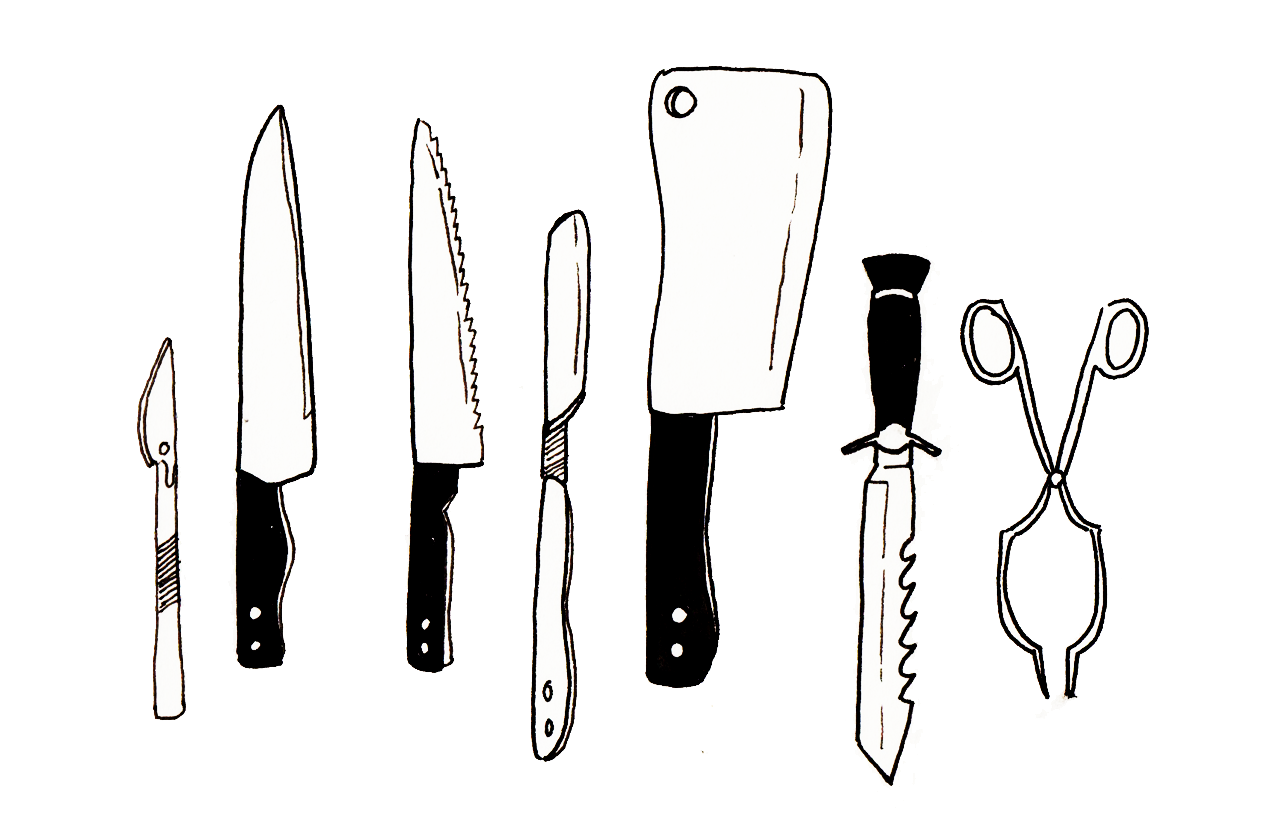

The cottage reeks of blood and metal, stains on the

walls and the sheets, the Hag rushes forward and

grabs for the Girl’s tiny hand, a hand so small it could

be taken in one bite; the bone easy to crunch through,

the veins slurped up like noodles. The Hag takes the

flailing arm of the new child, not more than ten

minutes old, forces the baby quiet and traces the

freshly formed lines of her palm.

“Sick, wasted thing,” the Hag hums. Mother’s eyes

bulge in fear, father snorts and grabs the Girl, but the

Hag has seen enough, “sick, wasted thing will be a

Hail Mary Girl, stacked like bales of hay, just like the

others.” The father confused, the mother exhausted,

they shake their heads and the man pushes the Hag

from the house. The baby wails and wails.

❦

The man was a farmer; radishes, carrots, large leafy

greens the rabbits would get to. He’d chase them off

with a wooden bat, too slow, but still saving his

produce goods. The Girl was sixteen by now with

sisters listed three behind her. She kept her mousy

brown hair long in one simple braid. A field of freckles

atop her nose and across her cheeks, crooked, big

teeth that made her look like the rabbits her father so

diligently chased. By now the Girl had suitors, she was

of age at this time; pages and peasants. Her

father, hoping to see her wed before his death,

counted them off one by one, insistent on finding the

perfect husband for his eldest daughter.

A market bears fruit and fish and simple greens;

the townspeople trade coins for delicate meats

wrapped in tawny paper. The Father sells his goods,

copper clinking in small bags dumped into dirty

hands fresh from the earth.

The Girl walks in line with her sisters, little ducklings

following their mother. She gathers the thigh of a pig,

fatty tallow, and bread. They make the butter

themselves. The girls do not wander out of line; the

villagers whisper about old men, maybe hermits or

knights that suck on their riches, spitting out metallic

dust. The girls do not wander out of line; large cliffs

surround the village, white foam waves along the

jagged rocks.

If only God would touch the town with one graceful

finger, with a cloak of gold, with a whisper to women.

How the sky turns red in the darkest part of night,

eyes like vessels carrying curdled milks. The Girl has

seen many men lick their lips, question her as she and

the other ducklings swerve from the market.

❦

A body is only the flesh it breathes; Christ on the cross

with the fresh birth of this sanctity. His flesh ripped to

shreds, real blood and salty liquor. If a good girl

follows the good God then she shall be a good wife.

The village square fancies gallows, fancies weddings,

fancies young women to the trust of old men. How

funny, the way the sun rises over the east wind, brings

with it dusted tales to waxed ears. What is sacrifice,

but a family heirloom?

Now, the man, Blue, named after the shade growing

from his chin, had been storing glass beads in his

beard, the hairs a deep blue and more course than the

Girl’s thighs. He had been stroking his beard until it

was able to lick the floor. He was forty tree rings old

with polished jewels on each milky finger, he popped

the dazzlers into his mouth like sweet cherries. This is

where the Girl saw the decay, how a tooth can lose its

will to attach to gums.

And then there was the castle.

The villagers had known about the depth of the castle,

high above the village center. Strapped into rocks and

eagles’ nests, corridors running like small rivers under

ice blocks of marble. The village people knew of the

deep lake running through his beard, the village had

always been in awe of the grey stone, the turrets and

rumored dungeons. The structure itself an omen, the

man himself a wolverine.

If the Girl had picked at the secrets like skin around

her thumb maybe she would have opened slow

instead of split like a small citrus. Her being so glossy

under scabs of dirt reached for stones tucked into her

gums; one tooth, two teeth, let the pink meat of her

smile dry out in the afternoon sun. If the Girl had only

remembered that she was just a young girl with soft

hair between her thighs and a belly like a soggy melon

– ripened before collapse. If she had known that she

was the tenth or eleventh or fortieth Hail Mary, would

she have entered?

Bluebeard gave the girl an amber ring set in a silver

band, a small spider frozen in the crystallized sap;

then he brought her to the castle. He gave her fabrics

made of human hair, silk with worms still alive and

glowing, he made the yard into an ocean so she would

wake to the sound of crashing waves. There was an

armoire carved from thick oak, an owl tucked into its

cabinet. In the hall there were many feasts, in the

garden were voles and peat to make the plants grow,

there were silver crowns and taxidermy boars,

swirled marble and acrylic paint.

Bluebeard was one day called to travel; something

about fabrics or spices and the Girl paid no mind. On

the day he left, he readied his horse and gave the Girl

the keys to the castle. He said, here, take these rusted

skeletons and use them for any room.

There were over fifty rooms in the castle, some filled

with spinning wheels, some with dolls, others had

musical instruments carved out of bone. His favorite

was the room dressed in wind chimes, like sitting

inside a bell, he said.

When he slid the keys onto the Girl’s boney wrist he

said, there are dreams upon dreams filling this

castle. Any room is yours, except the one with the

Oak door and iron casing. Bluebeard left a promise in

her hands, an X on the door, should the Girl enter, he

would know.

❦

The Girl and her sisters danced through the castle

until their spines began to rust. They lapped ice cream

from the dining tables and set off fireworks through

the halls. The Girl was a spinning top without nightly

visits from the coarse bearded tide; she walked with

shoes made from dust of Andromeda and swished her

dress celebrating every room of the castle.

The Girl and the three ducklings decided to give up on

their party when the last of the confetti had fallen,

when the wood floors became warped under spilled

wine.

There is the idea of curiosity. Women condemned

for their prying interests. How whenever a girl becomes

inquisitive, she will be left bruised.

It was then that the Girl crept down the last creaking

hallway, down the dim lit staircase, her carrying a

single torch and the ring of keys. There, there she

would find the door. Old oak in three slats, iron

plating curling around the top, a cold knob, and a

perfect glowing keyhole.

It was no surprise that when the Girl opened the door

she found the bodies of her predecessors. The man

had stacks of women, all curious about what lay

behind the door, their bodies piled, some still with

soggy flesh and some with jeweled rings spilling off

their bones. Skulls stacked in neat rows with gaping

mouths, missing teeth, severed necks. The Girl

covered her mouth from the stench and the key, to the

one forbidden room broke off the ring and dropped in

a pool of blood.

In a panic, the Girl fled. Begged her sisters to wash the

blood of the key after her arduous attempts had failed,

but the key was stained. Once silver, now a dull red.

The man would return and just like all the other wives

he would behead the Girl. How he would blame her

for being a curious child. For being a curious girl. For

being a girl.

❦

In the end, it was that she was all nerve endings and

salty meat, her mouth stayed watering for savory

juices and thick gulps of wine. She would not ask for

anyone to save her, she would not accept a grand

escape. All those Hail Mary’s that must be prayed, her

thumb locked in her mouth sucking on a Hag’s omen.

Sometimes we save ourselves until we cannot any

longer. That is how the girl fell. Without assistance

but still with strength like an angel welcoming a

hungry beast. The villagers eventually ran the blue

bearded man out of the castle. They dug many graves,

each body a bit of earth, each bone a place to rest. The

town gave white roses to plots, streaks of bright red

down the petals; they called out Hail Mary, blessed

are thou among women, the roses bled into the stone,

red pooled around the edges.

Nic Alea holds a fellowship from the Lambda Literary Foundation and was voted one of SF Weekly’s “Best Writers without a Book.” Nic has work featured in journals such as Muzzle Magazine, the Paris American, decomP, and others. They also read tarot, with special readings for poets and writers. Find more at nicaleawrites.com.