The Kill

The sinews stretched against the knife, fighting to keep the pieces connected to the whole, only to eventually sever with the pressure of the blade. And as we cut deeper, moving from muscle to organ, I noticed the heat still radiating from the freshly deceased. I was younger then, but I still remember the ephemeral expanse of perfection: the endless white of an untouched winter. I still remember the kickback of the rifle.

I do not remember the pursuit. I do not remember the shift from life into death. But there was a heart found within the beast, that as a child, I was told represented love and courage. So I held courage close to my own heart as our path of destruction ceased at a seeping sea of red, endless white now interrupted.

Once the chest cavity was empty I was shown the pool of blood collected in the void, a fountain of youth and sorrow. So we dipped our hands in the crimson cascade—newly found warmth in the height of winter—only to be confronted by the Kill slowly raising its head.

I retracted my hands, now covered in a film of shame. My father did not; he only stared the animal in the eyes and said, “I’m sorry, but . . . I just don’t think of you that way.”

“I know,” the Kill replied, “I just needed to hear you say it.”

I remember a carcass was later strung up in the garage. I do not remember going hungry.

The Ambassadors

Every hour, on the hour, a ghost train dissects my village. The tracks tell no tale of the passing monster, just cold steel laid to transport our coal-mining ambitions out of this rural prison: mountains the weathered walls, winter our warden. Every hour, on the hour, that whistle blows and I am torn asunder—whiskey my warm conductor.

I drink to the moon, I drink to the stars, and each night I sleep like a tie and have ambitions to die—two cold beams running along the crook of my neck and the bend in my knee. Each night I pray the humming is real, something more than this apparition, this hollow holy ghost.

The train stops once a year, the doom and gloom of a visiting darkness. The whistle still howls—every hour, on the hour—calling the saints to ready their day. And on this day, when the train stops, the township ambles to the tracks, like the promise of a parade, to see the haunting horrors. As the ambassador, I crawl off my bed to welcome our guests, the traveling circus of goblins and ghouls, banshees and abominations.

The demons though, they belong to us.

I drink. I drink like my father before me and his father before him, ambassadors just the same. The whiskey warms as the fires start, of house and home, of fur and of feather. The watchers wail to the plunder and curse, tears accompanying an occasional cough—

The coal mine will kill us all, like our fathers before us and their fathers before them. But that type of suffering works slow; tonight we just watch the devils dance—

And everyone looks to me, the man who sleeps with the trains, as if I could stop the charades. But this isn’t my mess, this isn’t my fight. I only go there, to the tracks, to die—if only in my dreams.

I look to the faces: the gluttons, the greedy, the ones who touch where their hands do not belong. These are the neighbors, the councilmen, the ones who watch our children. These are the faces that strip the land, rape the resources, and take without tribute. These are the faces that have forgotten animals still kick and scream when we slit their throats and drain their blood.

I drink to forget, I drink to forgive; I cough with them, but I do not sleep with them. They do not know I choose these tracks because I have more to fear than goblins and ghouls, banshees and abominations—

The train only stops once a year, but every hour, on the hour, it tears through me. I go to sleep at night, alone and asunder, the nape of my neck on the cold of the beam, knowing fully well there are far worse things in this world to have nightmares about.

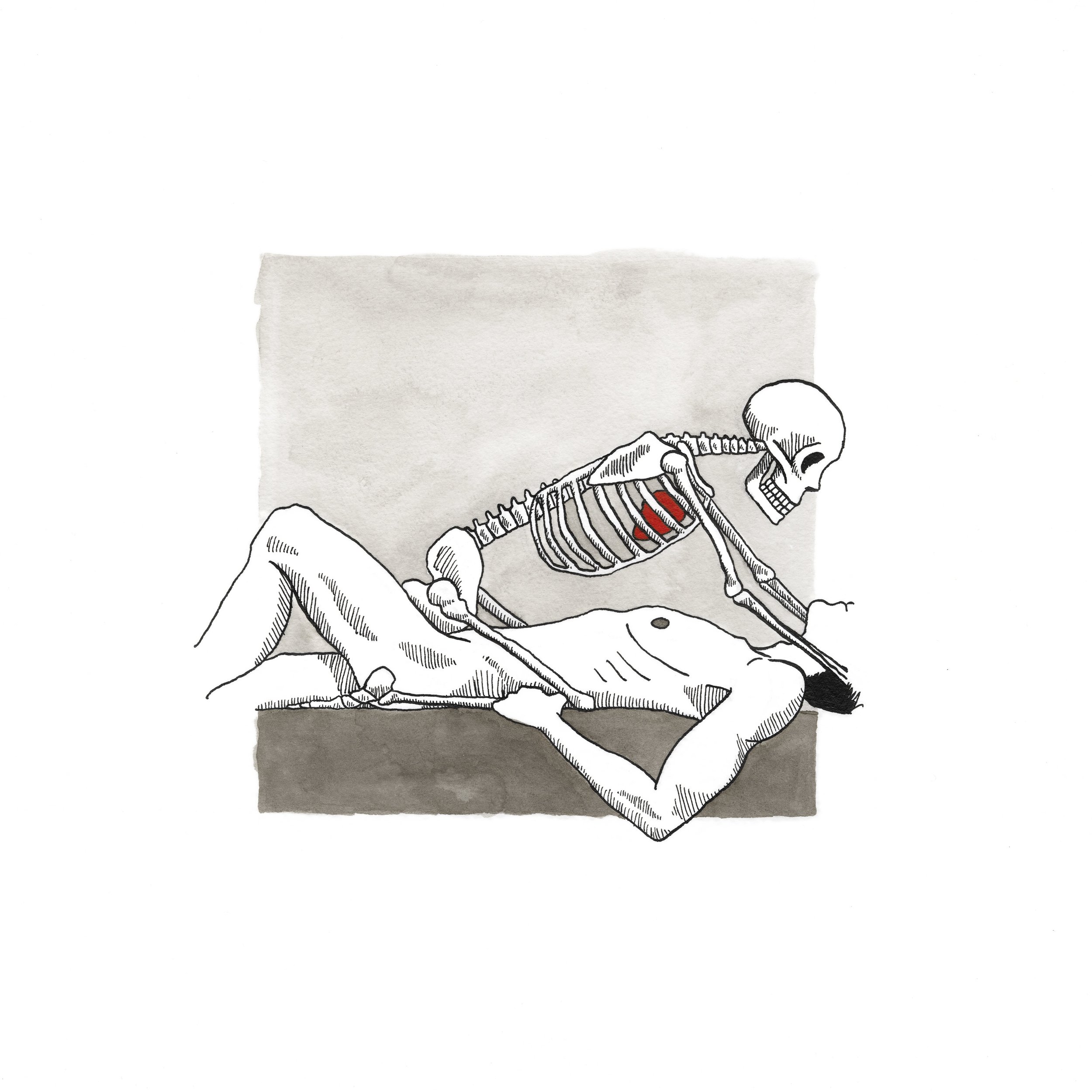

Grim Love

It was a vast assumption for Bard to believe the other man in the elevator was actually a man. This is because, as a product of Western culture’s TV programming (you know, shows like Family Guy), Bard had always thought the Grim Reaper to be a dude. But when Bard saw the Reaper, standing idle and pushing the heat-sensitive elevator buttons to no avail, gender wasn’t on his mind. All he whispered was, “Please, God, not today . . .”

The response wasn’t comforting: “Bard, holy shit, I’ve been looking everywhere for your sorry ass! I’m assuming you know why I’m here.” Bard didn’t respond though, mouth agape. All he heard was the voice, not the words, and it was that of a somewhat sexy female.

This he, sporting a tattered charcoal cloak and gripping a menacing scythe, was actually a she. Behind that skeletal face, one of every Halloween horror imaginable, resided the opposite sex of which Bard had spent the better part of his life trying to understand. He should’ve known it would be a woman sent to reap and collect his soul; after all, his two ex-wives had taken everything else.

The elevator then interrupted the man’s dumbfounded thoughts, buzzing to his obstruction between the doors. “Well,” Bard finally muttered, “we going up . . . or down?”

“That’s not really for me to decide. I’m just kinda here to kill you.”

“Can I at least grab one last beer?”

Death loosened her grip on the scythe, checked her watch. “I don’t usually do this,” she said, “but it’s a bit of a slow day. I suppose it wouldn’t kill us.” They both chuckled, making awkward eye contact as Bard leaned across her to push the elevator lobby button. It would have been a vast assumption at this point to ever believe these two would end up in love. But they did.

That night Death got way too drunk to kill Bard, as she is wont to do, and made a complete ass out of herself. Bard took her home, cleaned her up, and they fooled around a little. He then, after a minor debate on the issue, let her take the bed and him the couch.

The next morning Death slept till noon, late for the daily harvest, and donned sunglasses when facing the midafternoon light. She was too hungover to track down and kill Bard, but he left a note inviting her to make herself at home, that breakfast was waiting on the kitchen island. She played Call of Duty while waiting for him to come back. She smoked pot to pass the time. Once Bard returned, they sat together and killed CG Germans throughout the night. They made a good team.

Weeks passed, and yet, Bard lived. He took her dancing, on walks along the coastal cliffs, to archaeological lectures. They discussed politics, religion, and the unlikely possibility of time travel. Sometimes she would make him watch Sex in the City with her. Sometimes she would take him to the cemeteries and brag of her favorite assignments.

He would daydream of spending a life with her—having kids, growing old, the whole works. But Bard was already old. And he’d already made two attempts at such an existence, both failing: one to the folly of youth, the other to midlife dismay. Death was different, though. She renewed Bard, making him think he could do life all over again—and somehow get it right this time.

They made a good team, but this isn’t to say every moment was coming up roses. They would fight over petty bullshit, usually both drunk, with Death threatening to kill him and Bard threatening to kill himself just the same (out of spite, of course). They’d later joke and refer to such arguments as death-defying altercations. It was cute and they both knew it.

Despite the mutual obsession though, they still hadn’t made love yet—and it wasn’t due to any pragmatic lack of flesh either. Bard would tug at her cloak in fits, but she’d refuse. He’d send her provocative texts to no response. There was embarrassment strung across her bones, or maybe just hiding somewhere in that vacant ribcage of a chest, but she never confessed the shame—not even during the recurring inebriated nights.

“Why won’t you just fuck me?” he blurted one evening during foreplay. “Are you seeing other people? Is that it? Or is this just some sick game to you—something you do with all your victims? Huh? Is this just—”

She slapped him—

He open-mouth kissed her—

She pushed back—

He pulled her in. “Hey,” he said. “Hey,” grabbing her face, “please . . . please just be honest with me?”

To this she broke down, knowing the hurt she was fully capable of, and clutched him like the life she wanted so badly. “I used to be beautiful!” she lamented. “I hate what I’ve become. I HATE IT. And I could never give you what you need: I work strange hours, I’m moody, and my boss is such a dick—he really wants me to kill you!”

Bard grabbed her by the hand; he knew what it was to work for an asshole. “Hey,” he whispered, “just kill me when you’re ready . . . but please don’t drag this out.”

That night they made love like they’d been doing it for eternity, grace and ease lubricating the eccentricity. Death was nothing more than bones beneath that robe, but Bard handled every joint, knuckle, and spinal column with care. And when she would weep, thrusting aggressively and grinding her hips into his, he would draw her in, running a hand down her femur, and breathe her breath.

Thrust after thrust, dark orgasm after dark orgasm, they felt alive together, ravishing and abusing each other with only the lonely passion that flirting with death can bring. They tore each other apart, creating galaxies in the space between. He tasted her marrow. She, his mortality.

Bard’s body wasn’t found for nearly a week, not until the odor overtook his apartment complex and neighbors became concerned. The coroner’s reports ruled the matter a heart failure: poor diet compounded by inevitable aging. It would have been a vast assumption for anyone to think otherwise. It would have been a vast assumption to ever think the true culprit was the grimmest of love.

Tyler Dunning grew up in southwestern Montana, having developed a feral curiosity and reflective personality at a young age. This mindset has led him around the world, to nearly all of the U.S. national parks, and to the darker recesses of his own creativity. He’s dabbled in such occupations as professional wrestling, archaeology, social justice advocacy, and academia. At his core he is a writer. Find his work at tylerdunning.com.

Matthew Woods was born and raised in Massachusetts before being transplanted to New York City. He is a self-proclaimed Renaissance Man practicing many different art forms in various mediums. Never without a sketchbook in hand, he draws most of his inspiration from nature, horror, rock 'n' roll, and friends on a daily basis. Find him at matthewwoodsart.com.