They’re forcing us by video on the Big Screens to run fast again, “as fast as you can,” and if we choose not to it’s at the risk of great bodily harm and possible gruesome death. Very hard to ignore their order that way.

The Big Screens come on with loud volume musical accompaniment and there is an animation of an animated runner running for what looks like their life because of the terror conveyed through their body language—e.g., open-wide eyes, profuse sweating, frantic limbs moving with unnatural kinesthetic urgency. They don’t often compel us to do whatever it is they want us to do, but when they do, this imagery they employ is effective. I have to hand it to them, not that I agree with our being held here against our will and compelled to run at their whim on this large, circular track in the middle of an empty stadium.

This camp is in the middle of nowhere, and it’s so gray all morning, noon, and night. It’s very different in that way from the world we inhabited before we were brought here. My memory of that time is fragmented, but I do remember a few vivid details. The sky turned nightmare black at night, and every now and then the rain drizzled, which is still how the rain rains in this place (when it rains, which is not terribly often).

And nothing’s as bad as the final day there, when we were rounded up and shipped to camp. I remember that day very well. The worst was seeing strangers and some of our friends tied to trees, entrails pulled from their abdomens, blood pouring from their wounds. They had told us they didn’t feel like dying as we were marched past them. I don’t know if they died anyway, but I’d guess they probably did. Their entrails were exposed, and their blood was pouring out of their bodies. There was no obvious or good reason to treat them so brutally. It’s hard to imagine anyone deserves that kind of treatment, no matter what a person has done in their life.

❧

Believe it or not, despite all the misery, they’ve lightened up on us. Things are almost tolerable these days, if you can get past the frequent, random bouts of running. It leaves you with plenty of time to think, if you’re the sort that enjoys long moments of quiet respite.

I know I am.

I’ve gotten to thinking about why I was put here. Why were any of us? Who’s responsible? Nobody knows who put us here. At first I guessed it was aliens, and we were being treated like human livestock by a hungry race from far beyond our world. No. There’s no evidence of that. Bodies that die of their own internal causes are immediately vaporized by a beam from above, then a kind of mechanized “clean up” dustbin comes and sweeps up the ashes (and other dirt and debris), and that all gets collected in a giant ash and dirt heap in the northeast corner of the camp, up against the huge dividing chainlink fence that surrounds us and separates us from our freedom.

The heap is not guarded, so it’s hard to argue our dust is used for any specific end. Maybe they’re stockpiling it for something, but often the wind comes and blows a lot of it all over the camp and off into the greater world outside this prison, setting some of us free metaphorically (at least I like to imagine the detritus that way).

They’re also not efficiently systematically killing us off. Most of the people who die here are older, taken presumably by natural causes. And they’re encouraging us to partner off and mate, so it’s not like they’re trying to wipe out humanity. Maybe they don’t believe in humanity’s right to self-determination or something. But we’re about as free as we can be within the confines of this camp—an obvious contradiction, granted. It’s true, though. The only thing that really keeps us on our toes is the randomness of the forced running, and the violence that sometimes accompanies it. But then again, maybe that’s enough to achieve the end they desire, whoever they are. I guess it must be.

There are chessboards here. Meals are provided, and food is ample. This isn’t a prison in the usual sense. We don’t have cells or solitary confinement. It isn’t much of a prison camp, either. If the huge chainlink fence wasn’t barbed and electrified, escape would be easy. But even if the fence wasn’t barbed and electrified, it would only be escape into a vast, gray wasteland, getting drizzled on, presumably dying out there. If you did escape.

A few people have tried. Well, a few people have tried in earnest. Lots of people have “tried”—meaning lots of people have ended their lives on the electric fence, knowing full well that grabbing the fence mean certain death and preferring it that way. Suicide is common here, a fact I’d attribute to the gray and bland features of the landscape and the occasional moments of extreme horror, such as when seemingly random people are plucked from the track and thrown into the grinder, a rolling set of spikes held aloft on the north end of the stadium. This is surrounded by a cartoon cat videoboard (one of the many Big Screens)— the grinder serves as the inside of the cartoon cat’s mouth. The cartoon cat smiles, always, around the screams of the recent victim freshly ground. I still haven’t figured out why they make such a spectacle of the ones who are terminated. Perhaps they find it funny? Perhaps they wish to be amused.

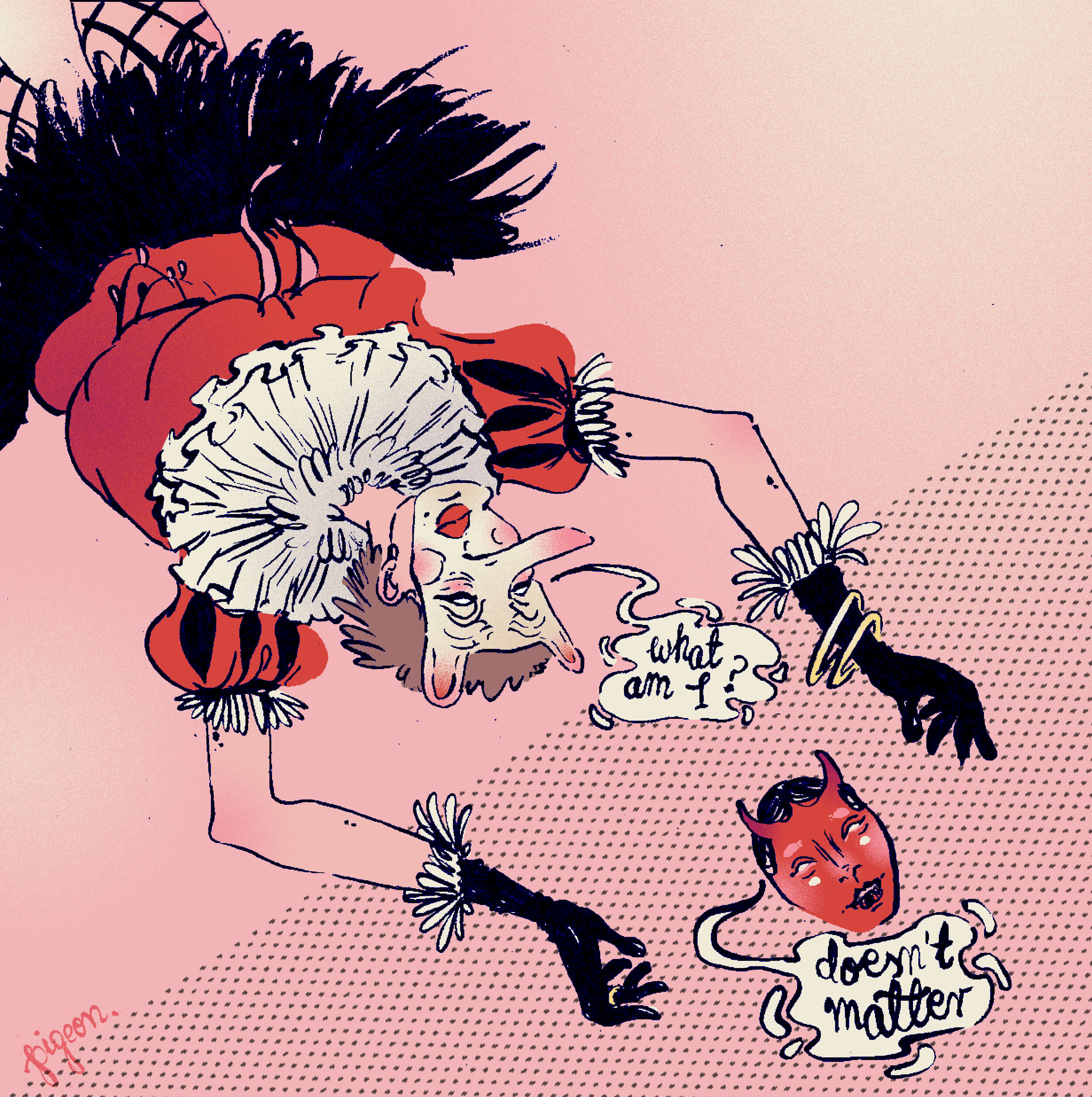

People have noted that the idleness and brief but profound moments of violence mirror the circumstances of fighting in war. I would liken it more to my idea of purgatory, with the caveat that here you can still die. I don’t know if death is possible in purgatory, but I also don’t believe where we are now is purgatory. I base my assumption only on a feeling. I have faith that this is not purgatory. I could easily be wrong, but I don’t think that I am.

We’re pretty disoriented. I doubt there’s even one among us who has successfully kept a tally of the amount of time we’ve spent here. We arrived one day all together, and it’s been like this ever since. No new prisoners. It’s hard to imagine there are very many people left on the outside. I suspect there are other camps. I suspect there is no one left outside of the camps.

One thing has changed. I don’t feel emotion like I used to. I still feel emotion, but I feel it very differently. A lot of the time I don’t feel it at all but when I do it is palpable. It is intense. I feel my insides screaming to escape my body. I writhe on the ground. My muscles clench, tighten, and then I am rigid, rigid with anguish. But I keep it all down. I get back up. I run mindlessly as commanded. Terror is the other feeling I notice from time to time, when not feeling either nothing at all or my insides knotted in frenzy.

❧

The Big Screens command us to run on the track once again. Something that can see us, sees all we are doing, at least while we’re on the track. I agree it might look to an observer like whoever is watching us watches us to see us race, but weirdly, we’re all wearing the same clothing with no marks to identify us, and we’re encouraged to run together by a floating wall of probes that shock us if we begin to lag behind or get too much of a lead out in front of the general herd. The uniforms we wear are a milky gray-beige. When we run we also wear helmets that block visibility of our facial features. The helmets are the same colors as our uniforms. We run for some undisclosed length of time and then a bell sounds and we are allowed to return to our routines. It definitely has something of an experiment about it, but one thing I’ve noticed is we’re always running more or less the same interval, time-wise: two hours (I’ve been keeping an approximate count in my head, despite the general disorientation I feel; it’s the one thing I’ve managed to do with consistency). We’re kept at roughly the same pace. Perhaps we’re the control camp.

❧

I play chess with Andy every day. After the most recent run, his hair is frazzled and he’s panting, catching his breath. He has told me he’s in much better shape than before we arrived here, but he’s still not in good shape. He’s said it’s likely he’ll never make very significant improvements physically, especially considering he eats a diet of fatty meats and cheeses. And his diet is not likely to change as long as those food options are still available in the cafeteria. He’s a bit more than a little overweight. He claims to prefer it that way. I see no reason to encourage him to change. Whatever happiness one can find here, one ought to take.

Andy told me about a dream he had recently during one of our games. “I was taking a shower. The dogs were barking. The wife was shouting. And there was a banging on the bathroom door. I remember thinking, shoot, they found out about my illegal activities and now they’ve come to make me pay the piper. But you know how dreams can be, from somewhere beyond normal a priori acquisition of understanding came the knowledge that that’s not why I was being arrested. I was being arrested for minor things I’d already been punished for. The authorities didn’t know the whole story. They didn’t know what I really deserved.”

When I looked down at our game he’d checkmated me, which is not uncommon.

❧

As for my own sleep, I have a recurring dream in which I’m visited by Resurrection Mary. In the dream she needs a ride. She needs to be dropped off at Archer Avenue, at the cemetery there. Everyone has heard some version of the story. The abandoned maiden picked up by a lonely traveler. She tells a story of being spurned by her lover, or some such occurrence.

Nothing’s strange about the situation, though I know she’s a ghost (that beyond-the-normal-acquisition-of-understanding in dreams). I talk to her about it, about all I know of her story.

“Why do you keep coming back here, after all these years? Why not move on?”

“Resurrection Cemetery is nice,” she replies.

“Yeah, but you’ve been here for nearly a hundred years. Hasn’t it gotten tiresome?”

“You make it sound like I can just leave.”

“Can’t you?”

“No.”

“Why?”

“Because it’s not that simple. Stop the car!” I stop the car. She lets herself out. We always arrive at Resurrection Cemetery. Mary says there’s so little I really do know. I agree, I emphatically agree. And I wish Mary well as she fades away.

What an involved dream I’m having, I often think, at that point in the dream.

❧

Then not infrequently I’m awoken and the Big Screens are demanding we run again.

A lot of the time, I’m happy to run. I’m glad to be compelled to run. I wasn’t very self-motivated before I was brought here, not enough to get myself exercising regularly, anyway. I am encouraged by how it increases blood circulation. Ideas come to mind more quickly when I run.

I finally decided I needed to at least attempt to escape. I decided it would be worthy to do it just to find out what would happen.

And I figured there might be an escape hatch, metaphorical or real.

Where.

The big heap of ash?

Would anyone even care if I were able to get to the other side of the electric fence? Would they wonder about me, the one who got away, when I was finally gone? Would the forces operating the Big Screens

There’s one guard tower but nobody’s in it, ever. You can even go up there. You won’t find an idle machine gun, or a thin thread of smoke trailing from the end of a recently set down cigarette, not a single trace of life. Believe me. I would know. I’ve looked.

I got a shovel. I began to dig, dig right into the ash heap. It became a hole, and soon I was digging through its very heart. Past bone shards. Absorbed by the pile of erstwhile humanity. It really did open up. It really did claim me.

Then I found an escape hatch.

It took me some days of digging, but eventually I split topsoil and arrived on the outer side of the prison fence. There, I had a vision of empty cities. Cities entirely devoid of inhabitants. Cemeteries without the bodies.

I heard the loud volume of the Big Screens and their musical accompaniment. It only took a moment and I was again crawling through the tunnel I’d made, this time heading back toward the camp.

Really, I was drawn back in.

Matt Rowan lives in Los Angeles. He currently edits Untoward Magazine and serves as interviews editor for Another Chicago Magazine. He’s author of two story collections, Big Venerable (CCLaP, 2015), Why God Why (Love Symbol Press, 2013) and another, How the Moon Works, forthcoming from Cobalt Press in 2019. He’s a contributing writer and voice actor for The Host podcast series. His work has appeared in >kill author, Pacifica Literary Review, Booth Journal, Necessary Fiction, and Gigantic Worlds Anthology, among others.