Dear Sir:

If you are reading this, I can only suppose that you have been cast into some deepest hell or purgatory in which you have to serve out your time by reading your fan mail. It must be a stack of infinite torment and weariness, of constant sickmaking praise and yawing depths of human need. I am sorry for your trouble. I do not wish to trespass on your time by telling you just how wonderful you are; I expect that you have been reliably informed upon this point. Instead, I want to tell you a story about hope. It starts with the National Lampoon.

I do not know whether you ever read the National Lampoon, although, if you are indeed in hell, I am sure it is available. When I was a little girl and I ran out of Mad magazines to laugh at, I found a number of my father’s National Lampoon magazines, and since they said they were humor magazines, I read them instead. They were where I first learned what was really funny, what men considered more hilarious than anything: women’s bodies. Women. Girls.

Girls were the joke; women were the joke. That was what I had learned on the playground, too, in the Mississippi Delta. Boys threatened me, hit me, pulled down my underwear, laughed at what they saw there. I wished more than anything that I was like Wonder Woman, that I had been born out on her magical island, where mothers asked the goddess for a daughter, and no one suffered boys.

There was, shortly after you left us, a great resurgence in interest in “Bohemian Rhapsody.” I do not know if you ever heard it was going to be in the “Wayne’s World” movie, or if you ever heard of “Wayne’s World.” You did not, in that respect, miss much. But it was very popular, and the characters in the movie loved that song; thus it was that young idiots such as myself, all over America, discovered it, and you. And I fell madly in love.

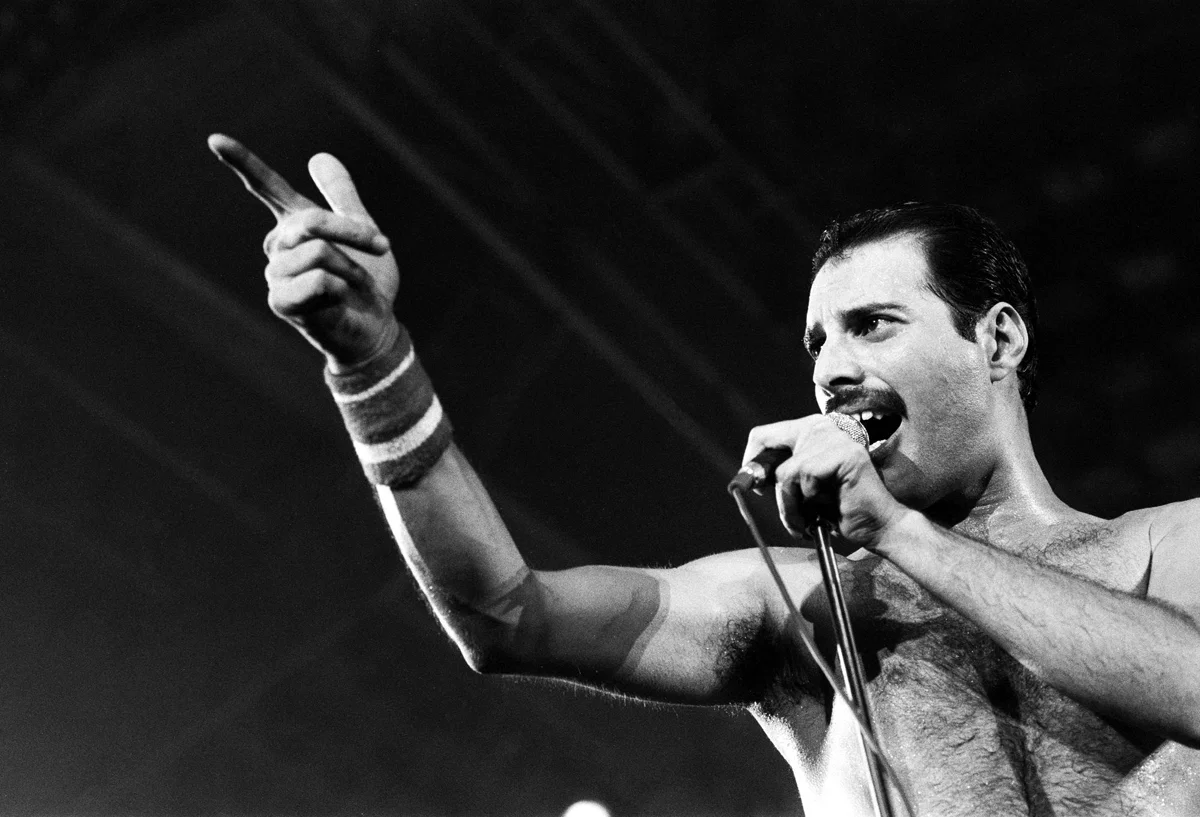

Of course, it was not you I loved. I loved Freddie Mercury. I did not and do not know you. It was only a course of a childhood disease, but I was twelve, and what could I do? You were magnetic. You were more of a man than I could bear to look at, almost. That did not stop me from buying magazines specifically to cut out the pictures and tape them to my wall. One of them I taped between the bars of my bedstead, where I could see it from my pillow, even reach to touch it. I knew my mother had to see where this was, and know why it was, and I did not care. So much was I in love, so much. I would listen to “Mustapha” with the lights out in my room, just to feel the keening in my skin.

The first man I had seen in such long black hair, such glittering outfits, and such stacked heels was Tim Curry, in The Rocky Horror Picture Show. But unlike Dr. Frank-N-Furter, who was cruel — who punished with sex, and was punished for it — the joy you offered was openhanded, without threat. Young Freddie Mercury was an emissary to me from another world, a place where sexuality was not mean or degrading, but exuberant and glamorous. I was surrounded by the indifferent, the lecherous jackasses of Mississippi, the cowboy hats of all America, and Freddie Mercury was a comet hanging Halley-distant in the sky.

My fever broke, as time went on, and my crush receded in due course. What I kept from it was a shard of hope — hope that desire could be bright and untainted, that there might be such a thing as joy for me. I came to need that hope. Even today, in middle age, I still have to be reminded that once it was.

We miss you very badly here, but you are, I dare say, well out of it now. Though I know that where you are, “dust is your food and clay your bread,” at least Theresa May is not your Prime Minister. Rest easy, then, and turn to another letter.

I am and will remain always

Your obedient servant

L.T.P.

L.T. Patridge, originally from Greenville, Mississippi, is a graduating MFA student in the Writing & Publishing program at Vermont College of Fine Arts. She writes Lovecraftian and historical fiction. Her novel The Innsmouth Ladies' Book of Household Management is available for pre-order from Kraken Press.