A Hybrid Poetry Series & Talk Originally Presented at the 2022 Visiting the Shadows Conference in Prague, Czechia

Exquisite Corpse at the Funeral, Taking Her Heels Off in the Grass, Blotting Her Mascara with a Xeroxed Copy of Psalm 23, Makes the Eulogy about the Survived By because Isn’t That the Point of Grief?

I plead guilty to ending all my poems

directing the audience to the nearest

light source, but we have to start elsewhere:

memory-eating black mold on door frames

Gramma couldn’t reach, Grampa’s mountain home

near the woodpeckers, then his home in memory care

where his Dementia invented tigers & hear

my Dad shooting at turtle doves, asking how come

Grampa insists on feeding the birds,

& now Grampa is gone & Dad fills each

feeder– wonder is contagious, poetic,

but memory is not, a redhead swear-worded

woodpecker belly laughs where I reach

the mountain peak, waxing prophetic.

Fold

I peaked in college & Mom hates my work clothes

but she loves Erin Brockovich, so sure, there is hope

as long as I expose a corporate scam & love a good man

who will never love my work, bride to whoever’s

Bic lighter & 9-24 months from now we’ll get Grampa’s ashes

& what hearth will hold his story & if nature is how

you say what is inherently part of us, then

every blue heron that finds me after every heartbreak

is my story. Winged nudge to tell Mom about the first girl I–

I know that Grampa knelt for each homily, & I know

his hands shaped church air, but that memory isn’t mine,

it was my Mom telling me, so when I say end with lightness,

I mean slit the poem’s throat with slats of streetlights glowing

through the blinds, those pillars I circled the night he died.

Fold

They say Gramma & Grampa circled the floor at weddings,

dancing all night, & forever in our living room, jitterbugging,

& forever his pink zinfandel with ice & forever I litter

memories on the wall like spaghetti to see if I’m ready

to watch that video of me singing for Grampa, 8 years ebbing

into diagnosis, his eyes closed like prayer hands, his feathered

jawline he drew in that self-portrait, his birds of an etc.,

& they say God gives you what you can handle, forgetting

that Gramma never wanted to marry, fools, she’d say, until

4 months in, honeymoon baby, sympathetic pregnancy,

& a wedding table teeming with Italian wedding cookies,

& that camera flash on their faces, hands thrilled

together smiling at future audiences, cake-slicing

& wonder isn’t narratively convenient, but he forgot anyways.

Fold

Once upon a time I was nineteen & growing out my hair,

Once upon a time, I was always just off my bicycle, body

odor, kazooing grass in the plum of my

thumbs. You sat with me in hospital beds, your

hand orbiting my ring finger,

& Grampa & I fishing in that memory

does not include me fishing or any

visual of Grampa, only the spector

of going, the Ford’s crank windows in my

hands, & it was 5 AM when I finally left the

home you & I made together, narrating

my steps to keep the story moving,

& I am going & I hope I carry pieces of him with me,

& I am going & I hope I carry pieces of him with me.

Fold

The second heron reminded me I was dumped in a cemetery,

& the first came in the way of long legs & considering how

my light is sent, I am ready to believe in God again, because

God is apparently a part of me, each heron dancing,

& the last time I saw him at memory

care, my brother patting his back softly, Gramma

crying & giving him Christmas gifts, Gramma

crying & kissing him on the cheek, I was thinking

of Grampa before all this, two feet on the pedal, Grampa

whose beard I scratched my face on, jumping

into his arms when I was little & the way his eyes would draw

in light when he said hey gal, & the animal I saw

in the woods the day after he died, & the animal nodding

back at me, how Grampa was there for me when he was already gone.

Fold

Gramma already gives me necklaces & to science, her body,

& Gramma sewed dish sponges until she washed off

her fingerprints & there are so many things I want

to ask that shapeless kindness that drove me to go fishing

but all I remember is the way the wind felt, the feeling

of being looked after & 9-24 months from now, we’ll send off

Grampa’s ashes in a Folgers can & we will all cough

in the dust of different, true men & what if “mummify”

didn’t mean embalm, but instead meant surround with mums,

& I don’t know if he lifted me on his shoulders to fill a

bird feeder or if I am remembering a toddler’s desire to be lifted,

& there are so many ways to tell his story & each is a true one,

his breadcrumbs beginning when he was alive, the blue heron still in

flight on the water, the streetlights’ violet children beside it.

Unfold

& when I say end the poem I mean slit the poem’s

homily & holds hands with God’s omens hissing out, air

Grampa doesn’t breathe, animal staring back at me, her

fingerprints’ absence, & there are so many things that hum

with the desire to be fed, & the bird seed remembers

the ground around it’s ring finger & the soil where

kindnesses are shaped by water & hunger’s

call & re-song & can we train our memories

to belong to us, because I am going & I hope I carry

freedom from him with me, & I am going & I

hope I bury reason – he forgot it anyways,

& Gramma used to say you’re a fool to marry,

& I saw a blue heron among the already dead,

& where light plays telephone, even mountains paraphrase.

*

I open with a poem because a poem is an incantation, is, in itself, a spell.

To call back to the last line of the poem, I was thinking so much about paraphrasing as I put this together. This hybrid poetry series and talk engages with the use of layering, layering poems onto theoretical text, as if layering clothing: a dress stuffed into pants to make a familiar silhouette unfamiliar, broader shoulders, the coil of extra fabric almost like packing. Layering also here acts as if crafting a sigil, as I sometimes do, layering consonants from the language of my intentions, to make the legible illegible. Witchcraft is inherently steeped in mystery, is a strategy of illegibility, and so I layer genres of writing here to emulate that defamiliarization.

At the 2021 Sewanee Writers Conference, poet Tarfia Faizullah said, “The value of the uncanny is facing what unsettles us.” I imagine you may have been here before, talking about the specter of the uncanny. It feels like an incredibly familiar subject, particularly in academia. But I am revisiting it again here, returning as a way of articulating my own experience of gender, in relation to the horror, dreamwork, relationality, and unsettling mechanisms of the uncanny.

When he first defined it, Freud wrote, “The uncanny is that class of terrifying which leads us back to the familiar.” In other words, the uncanny is the horror of what we know, what we have often been unwilling to recognize or return to, to look at more closely. Hearing Faizullah explain this concept, I was struck by Freud’s evocation of the language of heimlich/unheimlich. “Heimlich” translates as belonging to a house or family, as opposed to wild, and “Unheimlich” meaning uneasy, eerie, blood-curdling. In her talk at Sewanee, Faizullah points out that these terms are not antonyms; rather, unheimlich is an enhancement of heimlich, an addition to. The uneasiness of house or family. The eeriness of the familiar. It is a layering on to the initial term. I find this heimlich/unheimlich layering interesting because it demonstrates how I have tried to describe non-binaryness, not as transitioning from woman to man, or stereotypically androgynous in an imagined middle, but my own femininity as menacingly familiar, exuberantly off-kilter, an eerie extension of. Most famously used to characterize the robotic housewives in Stepford Wives, the uncanny is both domestic and terrifying. It defamiliarizes.

The uncanny valley, then, is a term that emerged in the 1970s, coined by Masahrio Mori, to articulate, as Faizullah put it, the revulsion in response to humanoid robots that are highly realistic. But today I am talking about my own experience of gender. I am a white, able-bodied, English-speaking American who was socialized as a woman. I identify as non-binary, and sometimes use the language of transness, but here I want to speak specifically to non-binaryness, because I think in a way I have not been able to find elsewhere, heimlich/unheimlich captures the enhancement I aspire towards in my own expression of non-binaryness, as opposed to transition between, or aspirations of faithfulness to an original, real thing.

Frankly, I have tired of the term “non-binary” and come to this subject because I am looking for new language. Non-binary is still a term that implements a binary, must exist in relation to the oppressive history of gendered binaries. I am trying to relocate what my gender exists in relation to – where my valley lies – my friends, pop stars I love, small aesthetic vignettes I build in my outfits and surroundings. My non-binaryness being relational doesn’t make it false, but makes it interconnected, adaptable, proof of an ever-shifting nature. My non-binaryness is perpetually liminal. For a long time I wanted to pin my identity down, be able to make it palatable. I wanted to be seen. To be legible, even just to myself.

I live in Knoxville, Tennessee, in the United States, where I am a student of poetry. It is March 2022 and in Tennessee, bill SB 2777 was just advanced, meaning that teachers could have legal protection to misgender their students. There is a simultaneous desire to be recognized, and also a violence in having to decide exactly who I am. Isn’t the wonder of non-binary expression to revel in what is liminal? To always be expanding?

In Seeing Like a State, James C. Scott writes, “Legibility is a condition of manipulation… Whatever the units being manipulated, they must be organized in a manner to be monitored.” To make myself legible to the state, to society, to the people around me, puts me in a position to be surveilled. The strategy of the uncanny, then, is one of liminality, caught between not anymore, and not yet (Barnie Risman). The uncanny is frustrating and unsettling because it is not discrete or contained. It is not definite. It troubles legibility. What is the simultaneous privilege or protection of being legible to the state, and the danger of it? Hasn’t trans history been one of slipperiness? Of oral retelling? Of layering estimations and liminalities? Or, as Leah Tigress has put it, “escaping the archive”?

*

I Begin & End with the People I Love

A Sonnet Crown on Non-Binary Legibility

Written in March 2022, after SB2777 is advanced in the state where I am a student of poetry

SB2777 would legally protect teachers to misgender their students

The first time she plucked my eyebrows: trowel

looting roots from my supraorbital

my sister made my tear ducts yowl

like twin wolves ballading silver comets

I made her prune them then with cuticle

scissors so instead of a removal

she pared back each brow hair: hemmed poodle-skirt

pervert garden bed stunted philia

Everywhere I walk seeds are possible

my sister pressed hours into metal

into quiet shapes so adolescence

could be beautiful for me I saddled

next to Mom to check it was legible:

those roots I kept: vernal: measured: lapels

*

The equinox prunes the darkness we’ve kept

All winter layers of lingerie wept

my body into being oh captain:

my Captain Crunch oh corset: my inflect-

ion of binders: difference made legible:

my eggshell hot pants ass slipping out egg-

cellent whites: life is enby D & slept-

in ball gowns road head girl gone wily fem

Leave behind my foreshadow: Wedding rice

Hair always growing out who decided

queer ethos means never getting there: Towards

being enough: Sappho won’t text me back

Gingko leaves press their ear sing to my lap:

[ ]

*

Tennessee sings for legibility

& whose song is my body sung for he

drums his fingers on my pronouns my breast

pocket introductory sticker most

call after me & cut my name in half

cup of sugar chorus catchy enough

to recognize after the first listen

student only of my friends expressions

To misgender: shards in the wrong window

To engender: forked seeds in a spotlight

To gender: to be that sexy singer

Who says Americana & means it

Who writes rock landscapes his shoulders live in

Soft for redemption: false premonition

*

When you touch me in my softest places / my hands follow you there: at first impulse / to protect: cover: gesture modestness / but I arrive & join your hands in praise

We discuss ampersands & you buy a / Heifeweizen: you know I’ll hate IPAs / Your sorghum spit your sweet hilt pants betray / What is whimpering but summoned bouquets

What is bucking but attempts at flora / I jogged myself chaste: body bearing a / resemblance to landscapes: thighs Palisades

or lithe as East Coast rain: saliva / shares a Venn Diagram with the Divine / placelessness spits on my strap-on: turnpike

*

Terrance Hayes said I have no form because

I have no allegiance to form the clause

of each fem in the pond skinny dipping:

thresholds for each other: unsaid: dripping

in sexual unmentionables: moon

machinists: we make kaleidoscope boons

of the ways they ruin us we ration

sky & still twang blue pond in our teeth in

our palm lines: I pulse with blood of women

I don’t know: liminal & eyelet lace

radius: decorata glass arbor vitae

[ ] percentage water costume jewelry

my friends call me into the pond my name

flashy too frivolous to be ashamed

*

I want my friends’ dreams to mean something big

meanwhile the state shakes us awake sprig

of lavender tucked in our pajamas

like knives still: Heather dreams of flying: awe-

stricken younger self watching: Brian dreams

of roller skating knees, red sky-gazing

Zenaida sends their joy-making playlists

& calls that a dream: Erin, who I kissed

in my own dreams, telepathically is

writing the same subject as me: kismet

prompts me to check my metaphysical

cupboards: jam jars turned water glass: recalls

Michelle Zauner’s women sharing trauma,

doing dishes & where are you: outlawed

*

I’m hem haw erotica but the law

would make me decide on discrete pink dreams

After so much time wanting to be seen

sex object syrup fantasy: declawed

Legibility my old dilemma

pet violence sprouting purple from dirt seams

Where my friends & I eat cherries sunbeams

Shellac is made from insect wings my jaw

shines smooth like road trip windows between states

friends’ couches chatter with my burlesqued name

My banana pepper blonde phase my bras’

push-up routine I could fit but my

people altar me: beautify me alive

dig up raunchy dimples: crude brows raised high

*

Questions I have asked before: do non-binary people just cast out the familiar? How can we return? Do I make the familiar unfamiliar? My poetry, my GNC friendships, are steeped in almosts, in puns, and resemblances, and mimicry of beautification rituals. I think here of the term “paronomasia” – that of a play on words, or a pun. I often feel I am trying to play a trick on the original phrasing. I enhance, make it funnier, grosser, distort it, do it wrong. Because often we are enhanced and made more of ourselves by each other, doing our makeup, practicing together. As Julissa Emile said in their keynote speech at the Feminine Empowerment Movement Slam Festival in 2020, we are realized in our friends’ mouths. So genders are communal happenings, relational, constellated expressions of gender. Feminine ritual is my witchcraft practice.

In “Exposing the Seams: Professional Dress & the Disciplining of NB Trans Bodies,” written by GPat Patterson and V. Jo Hsu, the authors define non-binary markings, one facet of this being that accessorization can act as self-assertion, and that “These accessories are not so much personal as social (V. Jo Hsu). They move through the article in stitches, sewing personal narratives together in order to reinforce their points. In this instance, the authors are referring to making their non-binaryness legible in the workplace – through trans flag stickers on their laptops, Pride posters on their office doors, pronouns in their email signatures. But I take the accessorization mentioned very seriously and literally, and want to emphasize that accessorization is a social act. Here, I accessorize with poems in a literary or academic space. I layer beautiful things, poems, images, associations with other artists until the sweetness is sickening. When I am the most in my gender, I am the uncanny valley girl. I aspire towards the dreaminess and oddity of the surreal. And what’s more is this is a spell that is done continuously with my grotesque and witchly friends.

Who has historically been called a witch? A big question that I will not answer in its entirety, but what feels true, is that those who have been called witches are those who are not performing womanhood in ways idealized by society. As I have begun to research collectivity, and relational understandings of gender, I have been drawn to the work of Surrealists Remedios Varo and Leonora Carrington, who were witches and painters and writers. They escaped Europe during WWII and met in exile in Mexico City. According to the National Women’s Museum of Art in Washington, DC, “Though they painted separately, they did spend time together cooking, writing spells, and looking for ways to prank guests. Their mutual interest in alchemy is evident in their works.” Although they were part of a formal art movement, they were described as “femmes-enfants.” I am heartened by that childlike spirit, and their willingness to get carried away, to wander. I think of “Exposing the Seams” again, and author V. Jo Hsu saying, “So often the genres through which marginal communities share and build knowledge are dismissed as frivolous or anti-rigor (social media, letters, zines, etc.) but these queer ‘ephemera’ are the means through which other worlds are made possible” (Hsu). Often it is the work of feminine people that is deemed frivolous. Home-making, party-planning, sewing, decoration. To perform frivolousness is to perform incorrectly in the eyes of the patriarchy, yet frivolousness was the guiding principle of Carrington and Varo’s friendship.

*

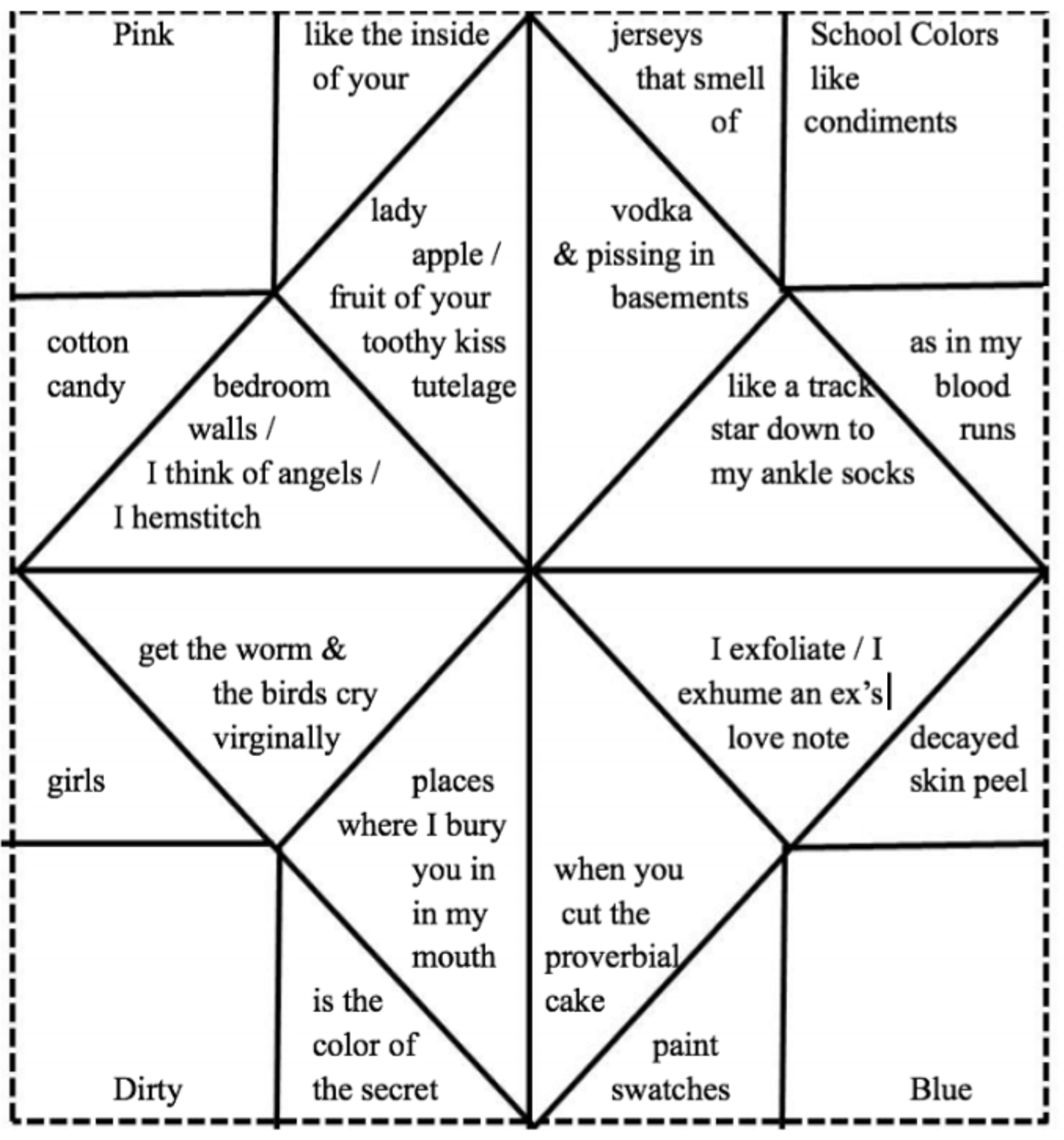

Exquisite Corpse as Cootie Catcher

After Tyehimba Jess

Leonora Carrington wrote a speculative Surrealist novel about her friendship with Varo, called The Hearing Trumpet. The protagonist, Marian, uses the hearing trumpet contraption her best friend Carmella gives to her in order to navigate her life in a nursing home. The novel troubles the line between experiencing Alzheimer’s and a surreality the audience might buy into. Another reason this novel means so much to me calls back to my first poem here, about my Grampa and the ways his softness was emphasized in his years post-Alzheimer’s diagnosis. His interest in the crape myrtle trees. His tears over the beauty of a cardinal. In one of the first scenes with Carmella, when the hearing trumpet is given, Carrington writes, “We both sat down and sucked a violet scented lozenge which Carmella likes because it scents the breath; I am now getting used to the rather nasty taste and beginning to like them through my fondness for Carmella. We thought about all the revolutionary possibilities of the trumpet” (8). I think here of how friendship acts as a boon through a traumatic experience, like being forced into a nursing home, and beyond that, demonstrates how the vision of our friends can guide us into a future that might not be imaginable on our own (Simone Breton). At the end of The Hearing Trumpet, Marian and Carmella live underground in a post-apocalyptic world. My friends make me more adventurous and, as I gather from this example, Carrington was likely emboldened by Varo’s imagination. Carrington and Varo were grounded in the domestic and the metaphysical, the intuitive and internal space, even in the face of a world which sought to get them to distrust that, to decide they were frivolous. In the novel, Carmella literally gives Marian the tools she needs to hear the world around her, and what is that, if not a sacred covenant between witches!

Part of the drop-off in the original diagram of the uncanny valley includes a corpse, and of course as I talk about non-binaryness I am talking through the very tangible danger of this way of being. You might have heard of an Exquisite Corpse before, a Surrealist game turned classroom icebreaker. It is a communally written story or piece of art, where the paper is folded, and participants respond to the line of writing or drawing immediately before them. I became interested in the form because of the body horror suggested by the name; the influence of surrealism used at its best for visionary, collective storytelling; the literal folds and interruptions and forgetting inherent to the form; and the contemporary everyday use of it to provide levity and connection. Where the state cannot and will not protect me, the non-binary people I love and I care for each other.

*

I Turn My Eyebrows Into Swamp Flora

Uncanny Valley Girl Glose

Electric green phosphorescent ointment

so said my hooded lids to handsome chins

my first night out, a la Amanda Lepore pout,

winged. My four thieves vigor carried off men.

Familiar, my budding performance, how

a scream is heard for what it is. Brood curdled.

Helicopter leaf. Stupefied beasts for brows,

bristling on my bark, my skin, my coffin.

Old medicine of sweet wine & egg whites

to build my appetite for last rites. Who’s saved?

There is no damsel left of me, just bio queen,

ornery rearrangement of flowers,

doppelganger of who I dreamed I’d be

when I was young, crinoline collapsing.

I didn’t kill the girl – I am reaching

for her still as she flies over the edge.

*

End Note: I used the glose poetic form in order to have something to respond to, a collaborative form, like the Exquisite Corpse. Each last line of each stanza is taken from the Leonora Carrington quote below. As the Exquisite Corpse is a game from the Surrealist tradition, I wanted to engage with her work.

“Some claim that the corpse was carried off by bees, & that

they have preserved it to this day in the transparent honey

of the flowers of Venus. Others say that the painted coffin did not

contain the princess at all but the corpse of a crane with the face of a woman,”

– “The Neutral Man” by Leonora Carrington

*

Although I am speaking about my own understanding of non-binaryness, I also believe that gender is constructed for all of us relationally, in how we are taught about our own performances and selves. I am wondering if I might invite you to take some time to make Exquisite Corpses in this space. When I first started writing them, people were confused that I wrote these poems alone. But for me, I always included quotes and lines and memories and aesthetics I learned from people I love. I believe to some degree we all start from those people, their movements, their gestures, their words. I am hoping I can invite you to start there now.

I think of the uncanny valley as a space for transmutation, where you take something and change it completely in form, so as to drop off the map almost of recognition, to unsettle. I think of the slant of the uncanny valley as it curves, the slant of my eyebrows from my frontal bone, the slant of arms on my friends as we lean into each other laughing so hard we are gasping, the slant way I talk about my gender to make it easier for other people, the slant of heimlich becoming unheimlich, the slant of camp and caricature in my expression of non-binaryness, the slant of witches who are not performing womanhood correctly, and so lean into something else entirely

❧

Sources (in order of appearance in essay)

Tarfia Faizullah’s Craft Talk on the Uncanny, Sewanee Writers’ Conference July 2021

“The Uncanny” by Sigmund Freud (MIT Press Online)

“The Uncanny Valley” essay by Masahiro Mori, accessed via a translation of the original essay by Karl F. MacDorman and Norri Kageki (Purdue Online)

Seeing Like a State by James C. Scott

Barnie Risman’s Venn Diagram of Legibility

Leah Tigress, @9BillionTigers. “Trans people have often had oral histories, subcultural relationships, and jobs in the underground economy. It is helpful for me (as a historian) to remember that not everything needs to be analyzed, that escaping the record is often the intent.” Twitter, Feb 5 2022.

Julissa Emile’s keynote speech, Feminine Empowerment Movement Slam Festival October 2020

“Exposing the Seams: Professional Dress & the Disciplining of NB Trans Bodies,” by GPat Patterson and V. Jo Hsu (The Journal of Multimodal Rhetorics)

“Artist Friendships: Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo” by Megan Masius, May 13, 2017. (National Women’s Museum of Art in DC)

The Hearing Trumpet by Leonora Carrington

Simone Breton, quote found at the Metropolitan’s exhibition Surrealism Beyond Borders

“The Neutral Man” from The Complete Stories of Leonora Carrington

Sara Mae is a high fem writer and style witch raised on the Chesapeake Bay. They are a 2022 Open Mouth Attendee, a 2022 Tinhouse Summer Workshops Alum, and a 2021 Sewanee Writer’s Conference Scholar. Their work appears in or is forthcoming from American Literary Review, Underblong, Pigeon Pages, Hobart and elsewhere. Their first chapbook, Priestess of Tankinis, is out via Game Over Books. They write shimmery rock music as The Noisy. They are currently an MFA candidate at UT Knoxville and an Associate Poetry Editor for Grist Literary Journal.